Hi, I’m Matt, and welcome to Steady Beats: rumination on music, muscle, and motion at midlife.

Deliver Me From Nowhere—and to Nowhere Else

I was seated on the cold bathroom floor tile, singing a new masterpiece.

I chose the bathroom because of the acoustics. The echo effect was enchanting.

(Actually, the bathroom acoustics were terrible. So was my voice. And the song was even worse.)

The lyrics of my creation, poured into a tape recorder, referred vaguely to the Olympics, and to “going for the gold.” That’s all I remember. And that’s much more than I wish I did.

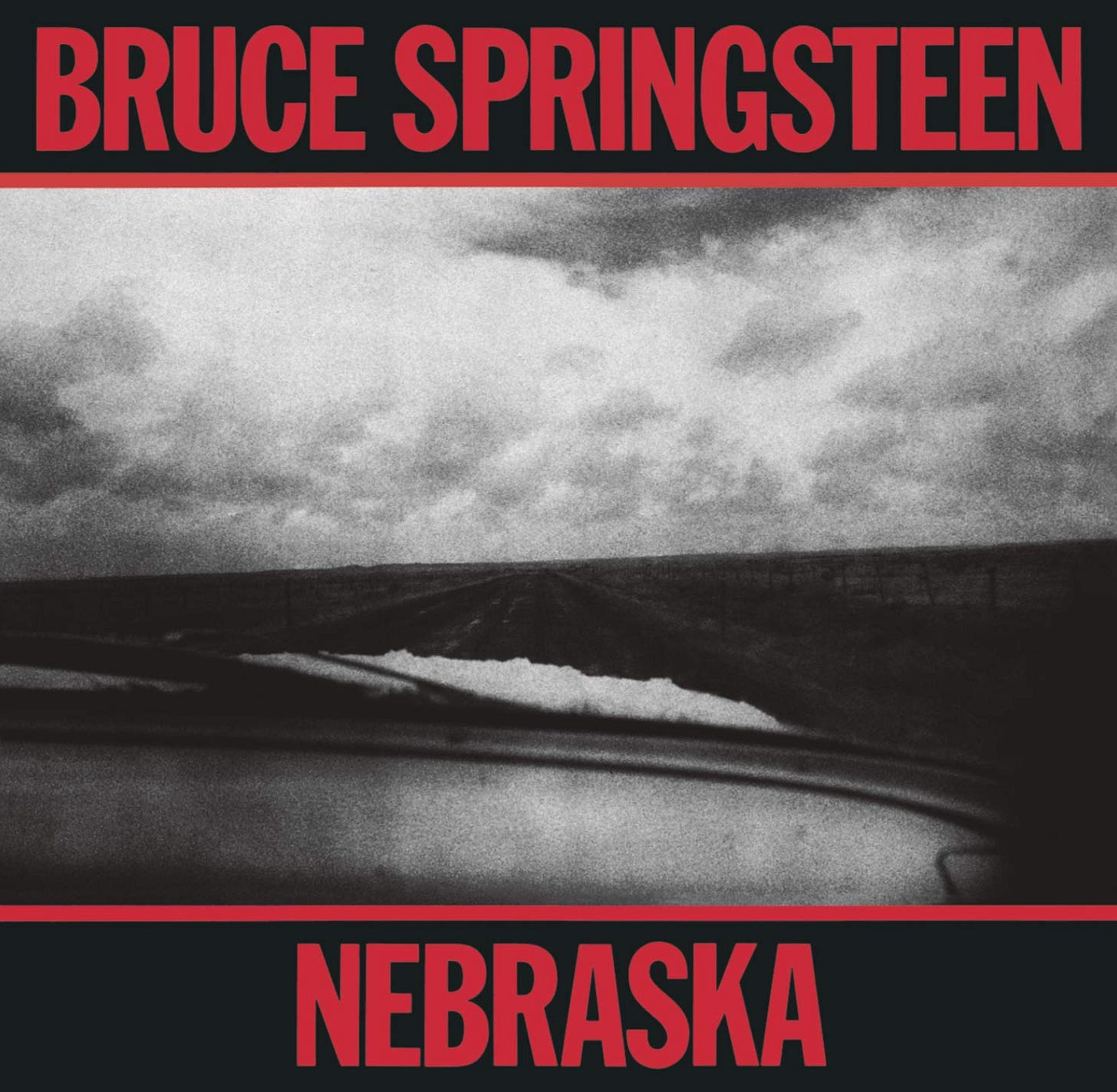

Meanwhile, around the same time, a slightly more talented artist named Bruce Springsteen sat in the bedroom of rented home in New Jersey, where an album’s worth of songs poured out of him and on to a demo tape, mostly on the night of January 3, 1982.

That’s the inciting incident of “Deliver Me from Nowhere,” Warren Zanes’ book which follows Springsteen into that demo recording session and on to the tortured attempt to professionalize the recordings thereafter.

We find Springsteen, grappling with the weight and isolation of fame, teetering on the edge of depression, as a series of songs came out—came through—Springsteen as he recorded demos alone on a new-fangled piece of equipment called a TEAC Model 144. He put the demos down on a cassette tape, and then set out to record them in-studio with his E Street Band, as was custom.

But the songs were stubborn.

The songs did not want to be messed with. It seems they weren’t his to alter—he was the conduit for their creation. As far as the songs were concerned, they were complete, enshrined in that cassette Springsteen carted around in his pocket:

Whether with the full band, with just Max Weinberg and Roy Bittan, even performing the songs alone, nothing seemed to capture the spirit of the cassette recordings. Perhaps the most troubling detail was that the songs weren’t even working as recordings when Springsteen played them solo. There was no band overpowering the songs then, so where did the songs go?

The songs didn’t go anywhere. They were right where they wanted to be.

Eventually, Springsteen decided to release the demos as the album. Even then, they had to be transferred to a master recording and mixed.

The songs did not budge.

Springsteen and team could not get the songs to transfer and mix without distortion. It was a time of emerging and incompatible technologies in the music business, the dawn of the digital age, and in the tech translations, the soul of the songs evaded every attempt to catch them.

For weeks the whole Nebraska album was, yet again, an uncertainty. It started to seem as if the recordings Springsteen had made were entombed in a cassette tape… inaccessible to anyone else.”

Eventually, Chuck Plotkin, who worked with Springsteen on “Darkness on the Edge of Town,” was brought in to solve the riddle. As Plotkin recalled:

“One of the things about Nebraska is it’s cut on a crap piece of equipment. It wasn’t a proper recording setup. It was also recorded by somebody who’d never recorded anything before. But they were making demos, so that wasn’t an issue. Then at some point it becomes clear that our efforts to rerecord the songs are not serving the material, that there’s something magical about this demo Bruce has made. And we have to confront the fact that instead of carrying on trying some other approach to bring back the magic—maybe we have the magic. So what are we trying to do? I just had to make it releasable.”

Plotkin did just that.

The album was on its way out of Springsteen’s pocket and on to critical acclaim and success—though Nebraska’s commercial impact was a fraction of what “Born In The USA”, with all it’s mid-80s pop and polish—would bring two years later.

“Writing is social,” as we like to say at Write of Passage. Nearly always, a creative work benefits from revision, from cutting and sharpening and input from others.

Nearly always.

Occasionally, a creative work comes out whole. Sometimes an artist will describe a feeling that the creative piece came through them: that they didn’t create it, but were merely the conduit. And once it’s out, it is complete.

How are we to know the difference?

I don’t know. Maybe the creative work itself has to tell us, sometimes with stubborn insistence. I believe that’s what the songs of Nebraska did.

Deliver Me From Nowhere, now slated for a movie release, is a no-brainer for anyone with a passing interest in The Boss and rock history. But it’s also for anyone interested in the messy, foggy, frustrating work of the creative process.

Thank you for reading edition #242.

Let’s keep the Steady Beats going. 💚

If you enjoyed this newsletter, would you mind giving the heart below a click?

As a young Black man from the South Side of Chicago, Bruce Springsteen was the first rock musician I 'heard'...the Marvin Gaye from the other side. I'd bought Born in the USA like everybody else, but it was Tunnel of Love that got me then and still does. Nebraska was a little too close to Grapes of Wrath but now I'm kinda ready for both...and Deliver Me from Nowhere

...the thing about Nebraska for me is how much it sounds like driving through Nebraska...whenever we used to tour through there we would put on that record and get somber and sloth the highway...an underrated aspect of music making is the tools people use to record...you get taught in music school how to do things the "right" way...but creatively doing anything only the "right" way is the wrong way to do it...you need to know your tools and not be afraid to break them and/or work with broken ones...the magic is in the performance, the content, the possibility, not the perfection...