The Mix Tape, Vol. 8

We’re back from Michigan, and readjusting to summer life in the Sunshine State.

Let’s wipe the sweat from our eyes, and march into Volume Eight.

The right way to break up Google

Google controls 92% of online search, but calls for “breaking it up” and/or regulation seem misguided.

Not that Google shouldn’t be regulated, but simply separating Gmail from YouTube from the search engine won’t break the company’s stranglehold on search.

What might, though, is forcing Google to open its search index to competitors:

Fortunately, there is a simple way to end the company’s monopoly without breaking up its search engine, and that is to turn its “index”—the mammoth and ever-growing database it maintains of internet content—into a kind of public commons.

There is precedent for this both in law and in Google’s business practices. When private ownership of essential resources and services—water, electricity, telecommunications, and so on—no longer serves the public interest, governments often step in to control them. One particular government intervention is especially relevant to the Big Tech dilemma: the 1956 consent decree in the U.S. in which AT&T agreed to share all its patents with other companies free of charge. As tech investor Roger McNamee and others have pointed out, that sharing reverberated around the world, leading to a significant increase in technological competition and innovation.

Doesn’t Google already share its index with everyone in the world? Yes, but only for single searches. I’m talking about requiring Google to share its entire index with outside entities—businesses, nonprofit organizations, even individuals—through what programmers call an application programming interface, or API.

Google already allows this kind of sharing with a chosen few, most notably a small but ingenious company called Startpage, which is based in the Netherlands. In 2009, Google granted Startpage access to its index in return for fees generated by ads placed near Startpage search results.

Corporate regulation is tricky. I have seen it from inside a particular industry, and the participants basically wrote some of their own rules, creating barriers for new entrants and pricing requirements that were dressed up as consumer protection.

Regulation can work, but it isn’t a magic elixir—especially if it isn’t well thought out, and doubly so when the regulated write some of their own rules.

We need to be careful about how regulation will really improve online discourse and data protections for consumers—and keep a close eye on who is really writing the rules.

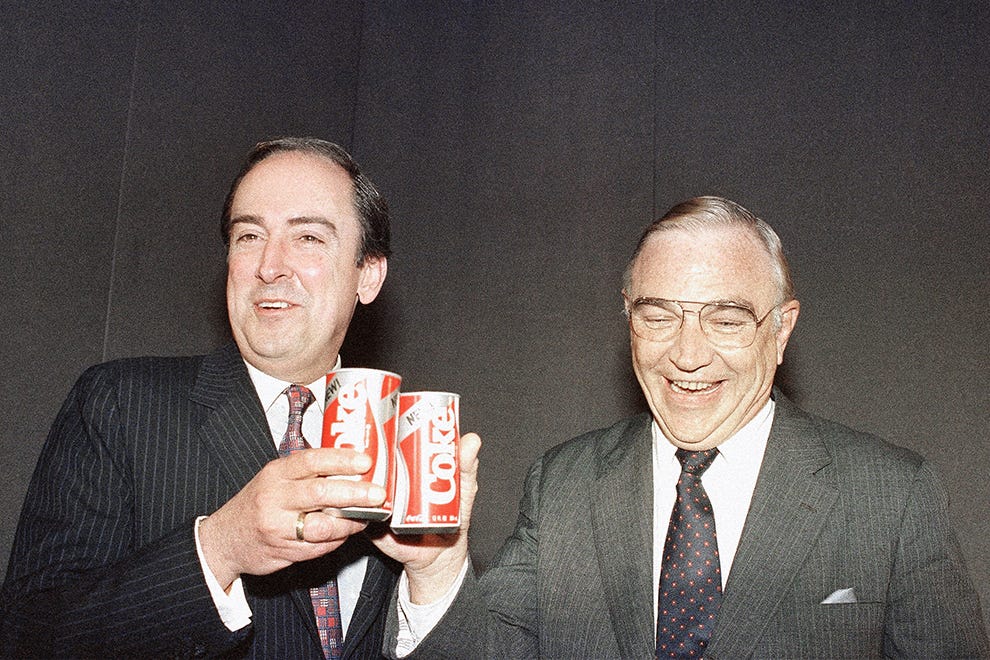

New Coke was not a massive marketing blunder?

Generally considered one of the worst marketing missteps of all time, “New Coke” was a sweeter, hipper version of the cola that rolled out in 1985, ending a 94-year run for the original version.

Two months later, facing extreme backlash (just imagine if Twitter had existed then) Coca-Cola brought back the original formula in its current “Coca-Cola Classic” iteration.

Tim Murphy has a new take on the New Coke mistake, though:

The popular version goes like this: In the early 1980s, not content with producing the world’s most recognizable beverage, greedy executives tweaked the recipe for the first time in 94 years. They redesigned the can, launched a massive marketing blitz, and promised a better taste. But Americans wouldn’t stand for it. In the face of a nationwide backlash, the company brought back the old formula—now dubbed “Coke Classic”—after two months. The story of New Coke is eternal. It’s a parable of hubris.

It’s also a lie.

Far from the dud it’s been made out to be, New Coke was actually delicious—or at least, most people who tried it thought so. Some of its harshest critics couldn’t even taste a difference. It was done in by a complicated web of interests, a mixture of cranks and opportunists—a sugar-starved mob of pitchfork-clutching Andy Rooneys, powered by the thrill of rebellion and an aggrieved sense of dispossession. At its most fundamental level, the backlash wasn’t about New Coke at all. It was a revolt against the idea of change.

Not saying I quite buy this next part—but it’s interesting:

Thomas Oliver’s 1986 book, The Real Coke, The Real Story, which is the definitive look at this saga, saw a strain of Southern reactionary politics in the backlash. “To them it was an extension of the Civil War,” he argues. “Here was Coca-Cola, a southern company, laying down its arms in deference to its Yankee counterpart.” Oliver means Pepsi, headquartered in Purchase, New York. He continues, “Coke, the quintessential southern drink, was changing its image and content to conform with the rivals in the North.”

That’s a little overwrought, but read the clippings and you realize he’s getting at something. “Changing Coca-Cola is an intrusion on tradition, and a lot of southerners won’t like it, regardless of how it tastes,” a University of Mississippi professor told the Chicago Tribune in 1985. “Why’d they announce it in New York?” wondered an Alabaman in the same story. It was another act of Northern aggression—a war between the tastes.

It’s common to believe the era of TV advertising was completely controlled by the corporations, a simple one-way communication exercise where consumers had little power and even less of a voice.

Whatever the exact elixir of circumstances that led to New Coke’s rapid demise, the story is a reminder that The People have always had a voice, even before we could Tweet, even when it came to pointless causes like sugary beverages.

(New Coke’s image rehab is being helped along by a marketing tie-in with the new season of Stranger Things on Netflix—in which the kids, in between chasing and being chased by monsters, chug New Coke.)

The wild new frontier of music marketing

Tom Petty’s 2002 album “The Last DJ” was mostly a giant middle finger to the music business and the hyper-control and greed he felt the industry enacted on artists and fans alike.

I wonder what Petty would make of music marketing today, which is more confusing and fragmented than ever, as personified by the rise of Lil Nas X and others fueled by the popular TikTok app:

The recent success of Lil Nas X is proof of this phenomenon. The 20-year-old rapper was a virtually unknown Tweetdecker when “Old Town Road” was embraced by TikTok influencers as the background music to something called the “Yeehaw challenge,” where users transformed into cowboys at the drop of a beat. Soon after the song went viral, Billy Ray Cyrus joined the track for a remix. In the three months since, their collaboration shot to the top of the Billboard Hot 100, where it has spent 12 weeks, matching the record of Drake’s similarly meme-fueled“In My Feelings.” After signing with Columbia Records, he debuted a high-budget, star-studded music video and announced a brand collaboration with Wrangler.

What is TikTok, anyway?

I went to someone in the target audience—my 11-year-old—and asked her to describe it. She said it was “just random videos, I don’t know, of all different things.”

True, but a little imprecise.

TikTok lets (mostly) kids upload short videos of lip syncing, dancing, or other “challenges” done to audio tracks—songs, usually—but sometimes to audio dialogue from TV shows, movies, or interviews.

The app has over a billion downloads, and is not meant for you, or me.

TikTok isn’t meant for the traditional record labels, either:

In a way, TikTok users are both the new A&R and publicity team, supplanting many of the functions traditionally performed by record labels. When Supa first discovered “Steppin” had blown up on the platform, he reached out to request that it officially be placed in its song-tracking system. (Before that, users were ripping the audio from YouTube, which made its growth hard to track and hurt the flow of listeners to streaming platforms like Spotify.) It was then that Mary Rahmani, TikTok’s director of music content and artist relations (and previously a director of A&R at Capitol Records), welcomed him with open arms. When I visited Supa in May, he’d recently returned from a trip to TikTok’s L.A. office. There, the company ran through his growth and numbers on the platform and offered him tips on how to better engage.

On the title track to “The Last DJ,” a distraught DJ escapes to Mexico to avoid a corporate radio stranglehold and play the songs he wants to play.

Today, that DJ would just pull out his iPhone and lip sync half a verse to whatever song he wanted. What a world.

Quick hits

Bruce Springsteen has a new album out called Western Stars. It’s a little bit country, but more Western. Its sound evokes images of Clint Eastwood peering over the mesa on his trusty steed. I like Tucson Train:

Last week, New York City experienced a blackout—42 years to the day after the infamous 1977 blackout. Generally, it sounds like residents made the best of it, and things were calm. Not so much in 1977, when a 25-hour blackout sparked riots and arson. Time Magazine has a lengthy article in its archives about the ‘77 event, and the New York Times has an interesting photo collage from that day.

The eloquent Ryan Holiday wrote a compelling essay on anger. He argues anger isn’t righteous, but makes everything worse—for you, and for our society at large.

Thanks for reading! See you next week.